Story number seven in the series ‘Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav – Celebrating seventy-five years of Independence’ comes from the North East.

The hero of this episode is U Kiang Nangbah. The term ‘U’ is used respectfully in the Khasi and Jaintia tribes of Meghalaya and pronounced like the Hindi syllable उ. This freedom fighter is from the Jaintia tribe. The Jaintias are also known as Pnars.

It is very interesting to see that throughout the territories of pre-independent Bharat, irrespective of the part of the land, the spirit of resistance to a foreigner was the same and therefore we find these patriotic gems in every part of our country.

The Jaintias are said to be one of the oldest tribes living in Meghalaya. The Jaintia kingdom consisted of the Jaintia Hills and plains called Jaintia Parganas. The residents of the hills were mostly the people of the Khasi and Jaintia tribes and residents of the plains were Bengali Hindus and Muslims.

Raja Rajendra Singh was ruling this area after his uncle Ram Singh. Rajendra Singh was asked by the British to sign a treaty with them to pay them a tribute of Rs. 10,000/- which the former refused to comply as he found it ridiculous. So in mid-March 1835, Captain Lister issued a proclamation, all of a sudden, that they were annexing the territory of the Jaintia Parganas. This meant that all the cultivable land went under the British control and the hilly region out of which not much income could be generated was left with Rajendra Singh. The king realized that this would not be financially viable and surrendered the hilly property voluntarily to the British and went and settled at Sylhet (which is presently in Bangladesh) with a monthly pension of Rs.500/-

Thus after the king was forcefully retired there remained just the ‘Dorbar’ – the council – which advised the king on his decisions.

U Kiang Nangbah was born in 1835 in a farming family in a place called Tpep-pale in Jowai which was the district headquarters of the Jaintia territory. His mother’s name was Ka Rimai Nangbah. Not much is known about his father.

U Kiang did not receive any formal education, but his mother personally taught him all that she could. Being a single child, he was greatly influenced by her, especially her patriotic fervor and freedom.

She often talked about the British and was worried that the foreigners would make them their slaves. This disturbed U Kiang very much.

In 1860, the British ordered imposition of house-tax on the people living in the Jaintia territory. The Jaintias were not used to paying any money to anyone earlier. The land was theirs. The houses were theirs. Even to their king, they used to send one goat and some measure of rice only once annually. This was totally new – a foreigner asking tax for what was not owned by them.

The citizens expected some sort of direction from the Dorbar in this regard as they were used to taking instructions from their king only. As there was no king now and with no clear instructions from the Dorbar they refused to pay the tax.

People who refused were beaten up badly by the British and some even died. There was no elected leader for the tribes then. One day, U Kiang happened to be present at his friend’s place just as the British had left after ruthlessly thrashing him. In front of Kiang’s eyes, the friend passed away after narrating what had happened.

Kiang was infuriated by what was happening all around. He met some of his friends and discussed about the problems created by the British.

The reason for taxes was ascribed by the British to the roads they had built but then, they had built it for transporting their soldiers and goods. The tribes had their own roads through the jungles. Also starting with a house-tax they could start taxing each and everything, felt Nangbah. If left unopposed, they would eventually become slaves of the British, he said. His friends realized the grave situation they were in. There were also rumours of income-tax which the British were considering.

Though the people revolted against taxes, the individual rebellion was being suppressed very easily and they needed to take mass action with a proper leader to lead them.

The British intrusion in the customs and practices of Jaintias had increased.

A police out-post and missionary school were established by the British near the cremation ground of the Jaintias. The Jaintias were then ordered by the British not to use the cremation ground citing the school and police out-post being located there.

The Jaintias were following their indigenous religion Ka Niam and they used betel-nut and betel leaf for their religious ceremonies. The British were also contemplating a tax on these items. The Jaintias had sacred groves which formed a designated part of each village. In these groves, the trees were venerated and no produce was allowed to be plucked. Though they were considered as places of religious significance, they were actually preserving the bio-diversity. The British and the Christian missionaries considered these as superstition and wantonly destroyed them much to the annoyance of the Jaintias who also felt it was an insult to their identity.

Soon, the members of the Dorbar held a meeting to choose a leader. After winning a diving competition at Syntu Ksiar in the Myntdu river, Kiang Nangbah was elected unanimously as the leader of the Jaintia tribes. He was also given authority to do anything to drive away the British.

Meanwhile the British intrusion continued unabated.

It is significant to note that in Bharat, like in other ancient civilizations, the practice of worshipping nature was uniform across native communities irrespective of the ‘religion’ followed by them. This was in stark contrast to the practitioners of the Semitic religions. And in fact, the intrusion of foreigners in local customs along with disregard and total mockery of the local practices and beliefs was a key factor which hastened the rebellion by the citizens in areas like the Jaintia Hills.

During their annual festival on the 29th December 1861, the Jaintias were prevented from dancing their traditional warrior dance Ka Pastieh in their festival at Jalong near Jowai. Under instruction of the British, policemen arrived at the spot and abruptly stopped the festival much to the shock of the community. Threatening the crowd which had gathered to witness the dance, they snatched away their swords, shields and drums used in the dance (which were highly venerated by the Jaintias), defiled and burnt all of them injuring people in the process. This was a great affront to the Jaintia tribe as a whole and their patience wore out.

Revolt against the British started. Within a couple of days, two British officers were killed, the police out-posts set to fire and their arsenal destroyed. Subsequently more and more damage was inflicted on the properties of the British like communication lines and warehouses and on the British soldiers. All this was done in such a secretive manner that the British intelligence agencies could not identify the trouble makers.

Raja Rajendra Singh who was in Sylhet was threatened by the British to reveal the names of the rebels as they were sure that he was aware of who the rebels were. However, he flatly refused to give any information on his fellow country-men and so he was sent to be imprisoned at Dhaka till his death. He died in April 1862 but somehow sent one of his soldiers to retrieve his ancestral sword which he had hidden somewhere and had it sent over to U Kiang Nangbah wishing him success in chasing away the British.

U Kiang Nangbah also travelled all over the Jaintia territory to garner support from all the villages. He openly called for complete withdrawal of the British from their territory. He said that if the British sought peace they should first leave the territory and peace would come on its own. British leaving?! There was no chance. And so there was more violence, now spread over in all the villages.

The Jaintias fought with traditional weapons like the sword and shield and spears and used guerilla warfare tactics. The chants in local language meaning “Sharpen your weapons and march! Let us drive out the foreigners” were heard aloud everywhere. U Kiang Nangbah organized and guided them excellently without the British knowing his identity.

The British did not know the complexities of the jungles and the hilly terrain which made it easier for the Jaintias to attack. For, they would attack the places of the British and run into the thick jungle cover and could not be caught. If the British chased them in the jungles, they would ambush the British. The Jaintia women did their part in nurturing the sick and cooking food for the warriors and carrying the injured to safer hide-outs.

Not able to face the tough fight, the British local administration handed over the Jaintia Hills to the British Army in March 1862. What they thought was some local disturbance was now like a full-fledged war and the British had grossly miscalculated the extent of the uprising. Also, they had recently suffered huge losses in the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny and its replication in various places. Again, hundreds of soldiers and horses were dying, and weapons destroyed now, in the fight with the Jaintias.

The British army now allocated about 2000 soldiers to fight the tribes and heavy loss was inflicted on the Jaintias. The battles continued and in one of them Kiang Nangbah was seriously injured in his leg. He went into hiding as he could not fight with his serious injury. He is said to have hidden in a place called Nartiang.

The British soldiers intimidated and even killed people in a bid to find out where U Kiang Nangbah was hiding but they were not successful. They then announced a handsome cash reward.

One of the persons of Nangbah’s team (some say he was a servant of a council member) by name U Long Sutnga overheard the council members speaking about the hiding place of U Kiang. Greed got the better of Sutnga. He went to the British and informed the hide-out of U Kiang Nangbah. Further he accompanied Lieutinant Sadlier with the soldiers of 28th Native Infantry division personally on 27th December 1862 to the hide-out.

When Nangbah saw the British and Long Sutnga together he immediately knew that he had been betrayed by his own clan and tried shooting Sutnga but the gun failed to fire. As Nangbah was already wounded and could not even walk properly, he could not escape. He was chained and brought to Jowai.

An ‘enquiry’ was conducted within three days by a Colonel B.W.D. Morton and U Kiang Nangbah was convicted (as expected) and hung to death on the same day that is 30th December 1862 at a local marketplace in Iawmusiang at Jowai.

U Kiang Nangbah was undeterred even at the time of hanging and before the execution, advised his countrymen to work hard and not forget the freedom struggle and to ‘chase away the foreigner’. He further said that after he was hung, if his face turned to the eastern side, our country would be free within a hundred years and if his face turned west, we would be enslaved forever.

It is believed that the face of U Kiang Nangbah turned to the eastern side.

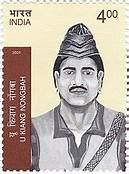

The date of his death is observed as ‘Martyrdom Day’ in Meghalaya and a memorial has been constructed for him at Jowai. The government also has issued a postage stamp in his memory in 2001.

My references for this story are majorly from a film of 2011, on this patriot, by Films division, Ministry of Information, GOI and few news articles and in particular, an article by Dr. Ankita Dutta who is a researcher on North-east Bharat.

Usha Pugal

thank you Vidya. we know few patriots only but now understand how many unknown warriors were there behind the battle

krvidhyaa

Thank you very much Usha! That was the purpose of writing this series!

RamMohan

Nice and well researched. Also brings out little known personalities from the North East to the mainstream Indian audience

krvidhyaa

Thank you Ram Mohan!!

R. Latha

very nice vidhya. unknown stories about patriots who gave their life for the country.

krvidhyaa

Thank You Latha for reading and giving feedback!

Gomathi S

Thank you for writing about less known freedom fighters Vidhya. We appreciate the efforts taken by you . Keep up the good work.

krvidhyaa

Thank you Goma!!